Part IV: The Dream Teams – The Olympic Modern Era & NHL Expansion (1992 -2014)

In addition to being called the “Modern Era” of Olympic ice hockey, I also call this the “Fantasy Hockey” era. For the first 70 years of Olympic history, the rosters were dictated by politics and loopholes (as covered in greater detail in Parts I, II, and III of my ‘Olympic Hockey Era’ series). But starting in the late 90s, the Olympics finally became what they were always meant to be: the greatest players in the world, regardless of contract status, fighting for national pride.

I find this timeline to be some of the most nail biting hockey to current date because the stakes became impossibly high. When you put Wayne Gretzky, Sidney Crosby, Jaromir Jagr, and Teemu Selanne on the same ice, the margin for error disappears. A single bounce, a single shootout attempt, or a single goal in overtime can define a legacy.

This era is special because it gave us closure. We stopped wondering who was actually the best. We saw Canada end a 50-year curse, we saw the Czech Republic shock the world, and we saw the United States and Canada forge a rivalry so intense it shut down entire countries during the Gold Medal game.

Here’s a quick snapshot of all the Olympic hockey results for this era:

Olympic Medalists: The Modern Era (1992–2014)

| Year | Host City, Country | 🥇 Gold | 🥈 Silver | 🥉 Bronze |

| 1992 | Albertville, France | Unified Team | Canada | Czechoslovakia |

| 1994 | Lillehammer, Norway | Sweden | Canada | Finland |

| 1998 | Nagano, Japan | Czech Republic | Russia | Finland |

| 2002 | Salt Lake City, USA | Canada | USA | Russia |

| 2006 | Turin, Italy | Sweden | Finland | Czech Republic |

| 2010 | Vancouver, Canada | Canada | USA | Finland |

| 2014 | Sochi, Russia | Canada | Sweden | Finland |

Now to the fun stuff that helped define the current era of Olympic hockey.

Table of Contents

I. The Transition Years: 1992 & 1994

Before the NHL fully committed to the Olympics, two “bridge” tournaments took place that were defined less by corporate sponsorship and more by the chaotic geopolitical landscape of the early 1990s.

1992 Albertville: The “Ghost” Team

Dates: Feb 8–23, 1992

Venue: Méribel Ice Palace (Albertville, France)

The 1992 tournament was played in a political vacuum. The Soviet Union had officially dissolved in December 1991, just weeks before the Opening Ceremony. This left the greatest hockey dynasty in history without a flag, an anthem, or even a country name.

- The “Unified Team”: To keep the roster intact, the former Soviet states (Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, etc.) agreed to compete as the “Unified Team” (EUN) under the Olympic flag.

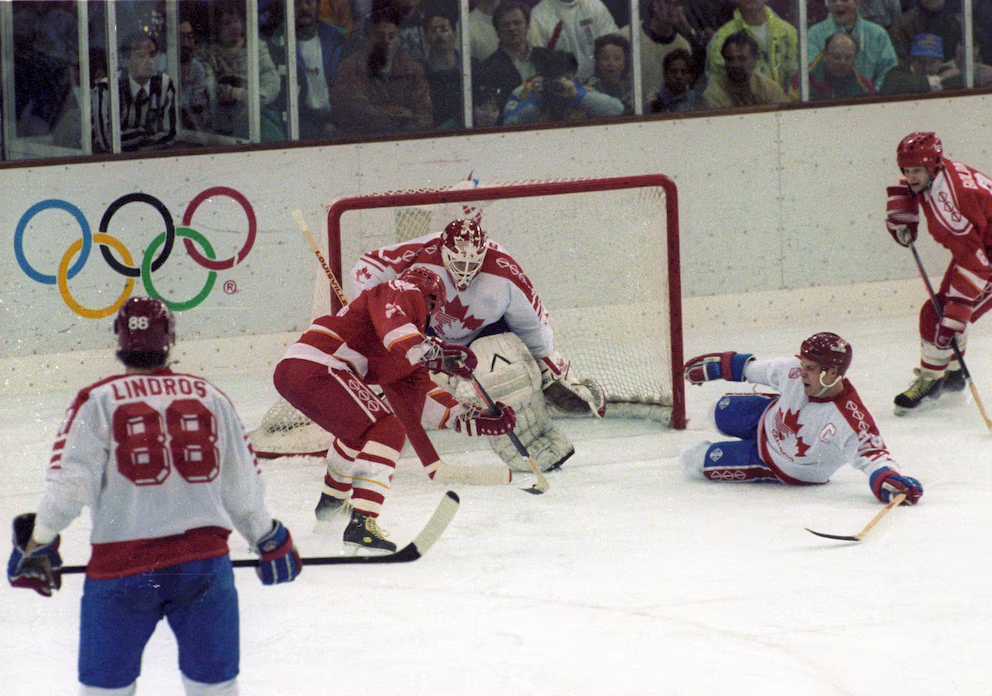

- The Result: Despite the turmoil back home—and a roster depleted by the defection of stars like Sergei Fedorov to the NHL—the Unified Team played with a desperate cohesion. In the Gold Medal game, they faced a Canadian team led by the 18-year-old phenom Eric Lindros (who was holding out from the NHL at the time). The “Ghosts” won 3–1. When the Gold medals were handed out, the Olympic anthem played instead of the Soviet anthem, marking the final breath of the Red Machine.

1994 Lillehammer: The Forsberg Stamp

Dates: Feb 12–27, 1994

Venue: Håkons Hall (Lillehammer, Norway)

By 1994, the Soviet Union was gone, and Russia competed as an independent nation. However, the story of Lillehammer belongs to Sweden. The Gold Medal game between Sweden and Canada ended in a 2–2 tie, forcing the first-ever shootout in an Olympic final.

- The Move: In the decisive round, 20-year-old Peter Forsberg skated in on Canadian goalie Corey Hirsch. Forsberg drifted to his left, sliding the puck with one hand while his body went the other way, and tucked it into the open net—a move he later admitted he learned from watching Kent Nilsson.

- The Legacy: Hirsch couldn’t recover, and Sweden won its first Olympic Gold. The goal was so culturally significant that the Swedish government issued a postage stamp depicting the move. However, because Forsberg was wearing an “NHL-style” jersey in the photo, the stamp artist had to change the number and jersey color to avoid copyright infringement.

II. 1998 Nagano: The “Tournament of the Century”

Dates: Feb 7–22, 1998

Venue: The Big Hat (Nagano, Japan)

This was the watershed moment. For the first time in history, the NHL paused its season for two weeks, allowing the absolute best players in the world to compete. The rosters read like a Hall of Fame ballot: Gretzky, Yzerman, Bourque, Selanne, Jagr, Bure, Modano, Hull.

The Czech “Left Wing Lock”: While Canada and the USA were busy building offensive “Dream Teams,” the Czech Republic built a fortress. Led by coach Ivan Hlinka, they played a disciplined, trapping style that frustrated North American skaters. Their ace in the hole was Dominik Hasek, a goaltender whose unorthodox “flopping” style was revolutionizing the position.

The Shootout Controversy: The semi-final between Canada and the Czech Republic is arguably the most analyzed game in Canadian history. After 60 minutes and overtime, the score was tied 1–1. In the shootout, Hasek was invincible, stopping all five Canadian shooters (Fleury, Bourque, Nieuwendyk, Lindros, Shanahan).

- The Decision: Canadian coach Marc Crawford famously left Wayne Gretzky—the NHL’s all-time leading scorer—on the bench for the shootout. Crawford later justified the move by citing Gretzky’s poor breakaway stats that season, but the image of “The Great One” sitting alone on the bench while his team lost remains an open wound for Canadian fans.

The Result: The Czechs went on to defeat Russia 1–0 in the Gold Medal game, securing the first Olympic Gold in their nation’s history. When the team returned to Prague, hundreds of thousands of people filled Old Town Square, chanting “Hasek to the Castle!” (implying he should be President).

III. 2002 Salt Lake City: The Curse Breaker

Dates: Feb 8–24, 2002

Venue: E Center (Salt Lake City, Utah)

The pressure on Team Canada in 2002 was suffocating. They hadn’t won Olympic Gold since 1952 (50 years). The media scrutiny was so intense that after a 5–2 loss to Sweden in the opener, Executive Director Wayne Gretzky launched a famous tirade at a press conference, claiming the “whole world wants us to lose” to galvanize the team.

The “Mario” Play: The Gold Medal game against the USA (on American soil) was a classic. The score was tied 1–1 in the first period. On a Canadian rush, Mario Lemieux—who was battling severe hip pain—saw Paul Kariya streaking behind him. Instead of touching the puck, Lemieux let the pass go through his legs, completely fooling the American defender and goalie Mike Richter. Kariya buried the shot. It is widely considered the greatest “non-assist” in hockey history. Highlight provided below.

The “Lucky Loonie”: After Canada’s 5–2 victory, a legend emerged. Trent Evans, an Edmonton-based ice maker hired to maintain the rink, revealed he had secretly buried a Canadian one-dollar coin (a “Loonie”) at center ice before the tournament began. He claimed it was for good luck. The coin was dug up after the game and eventually placed in the Hockey Hall of Fame.

IV. 2006 Turin: The Swedish “Double”

Dates: Feb 15–26, 2006

Venue: Palasport Olimpico (Turin, Italy)

While 2002 was about North American emotion, 2006 was about Scandinavian precision. This tournament saw the collapse of the heavy favorites (Canada finished 7th, USA finished 8th) and the rise of a new European power.

The Swedish System: Sweden, led by Detroit Red Wings defenseman Nicklas Lidstrom and Toronto Maple Leafs captain Mats Sundin, played a game of flawless possession. In the final against Finland (a fierce Nordic rival), the game was tied 2–2 in the third period.

- The Goal: Lidstrom blasted a slap shot from the blue line just 10 seconds into a power play. The puck famously hit the crossbar and went in. Sweden held on to win 3–2.

- The History: With this victory, Sweden became the first nation to win Olympic Gold and the World Championship Gold in the same year, a feat known as the “Double.”

V. 2010 Vancouver: The Golden Goal

Dates: Feb 16–28, 2010

Venue: Canada Hockey Place (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada)

For Canadian hockey fans, history is divided into two eras: before 2010 and after 2010. For my drama lovers, the pressure on this team was unlike anything seen in the modern era. The Olympics were on home soil and the tournament boiled down to a Gold Medal rematch between Canada and the USA. The hype and pressure had everyone on edge.

And if that wasn’t enough pressure, the Canadian government had launched the “Own the Podium” initiative, explicitly demanding Gold Medals. Anything less than victory would be considered a national humiliation.

The Narrative Arc: The tournament did not start well for Canada. In the preliminary round, they lost 5–3 to the United States—a young, fast American team led by goaltender Ryan Miller, who was playing the best hockey of his life. That loss forced Canada into a harder elimination bracket, where they had to crush Russia (7–3) just to get a rematch.

The Game: The Gold Medal Final was watched by an estimated 26.5 million Canadians—roughly 80% of the entire population.

- The Lead: Canada played a disciplined game, taking a 2–0 lead on goals by Jonathan Toews and Corey Perry.

- The Comeback: The Americans refused to die. Ryan Kesler scored to make it 2–1. Then, in a moment that sucked the air out of the entire country, Zach Parise banged home a rebound with just 24 seconds left in regulation to tie the game.

The Moment: Overtime was played 4-on-4, creating open ice for the world’s best skaters.

- 7:40 Mark: Sidney Crosby dumped the puck into the American zone. He didn’t chase it; instead, he drifted toward the net.

- The Battle: Jarome Iginla, battling two American defenders in the corner, dug the puck loose.

- The Shout: Television microphones clearly picked up Crosby screaming “Iggy!” to call for the pass.

- The Shot: Iginla fed a pass to Crosby, who was below the faceoff circle—a bad angle for a shot. Instead of dusting the puck off, Crosby fired a snap shot instantly. The puck went through Ryan Miller’s legs (the “five-hole”) before the goalie could even react.

The Aftermath: The goal didn’t just win a medal; it released weeks of national tension. Reports later confirmed that the collective cheer was so loud it registered on local seismographs in British Columbia. For the “Nintendo Generation,” this was their version of the 1972 Summit Series—a defining “where were you when” moment that cemented Crosby’s legacy as the heir to Gretzky.

VI. 2014 Sochi: Tactical Perfection

Dates: Feb 12–23, 2014

Venue: Bolshoy Ice Dome (Sochi, Russia)

If Vancouver 2010 was a heart attack, Sochi 2014 was a surgical procedure. The 2014 Canadian roster entered the tournament with a singular goal: to prove that they could win on the larger international ice surface—something Canada had not done since 1952.

The Philosophy: Head coach Mike Babcock implemented a system that was radically un-Canadian. Instead of the traditional physical, forechecking style, he demanded total puck possession. The strategy was simple but arrogant: The other team can’t score if they never touch the puck.

- The Defense: The blue line was anchored by Shea Weber and Duncan Keith, but the real story was Drew Doughty. The LA Kings defenseman played arguably the best hockey of his career, controlling the pace of the game so effectively that he often looked like a fourth forward.

The “Boring” Dominance: Critics at the time called Canada “boring” because they weren’t blowing teams out 10–0. But they don’t know hockey. If you ask me, the stats tell a story of suffocation. Canada never trailed for a single second during the entire tournament.

- Goals Allowed: They gave up only 3 goals in 6 games.

- The Semi-Final (vs. USA): This was expected to be a shootout. The American offense, featuring Phil Kessel and Patrick Kane, had been scoring at will (20 goals in 4 games). But in the semi-final, Canada simply deleted them. The USA managed only a handful of dangerous shots. Canada won 1–0 on a goal by Jamie Benn, but the score flattered the Americans. It was a clinic on how to neutralize speed.

That said, even the highlights are kinda boring…

The Final (vs. Sweden): Sweden was the only team capable of matching Canada’s depth, but they were dealt a crushing blow just hours before the final: their star center, Nicklas Backstrom, was suspended due to a failed drug test (later attributed to allergy medication).

- The Result: Without their playmaker, Sweden had no answer for the Canadian machine. Jonathan Toews scored early, Sidney Crosby scored on a breakaway (his first goal of the tournament), and Chris Kunitz added a third.

- Carey Price: The Canadian goaltender was so protected by his defense that he barely had to move. He finished the tournament with a 0.59 Goals Against Average and a .972 Save Percentage. (Is that a good save percentage?)

The Verdict: When the buzzer sounded on the 3–0 victory, there was no frantic pile-on like in 2010. The players simply hugged, business-like. They knew what the world soon realized: this wasn’t just a Gold Medal team; it was a team that had “solved” the game of hockey.

The Rise of Women’s Hockey (1998–2014)

For decades, women’s hockey existed in the shadows—unfunded, unrecognized, and often actively discouraged. That changed forever in 1998 when the sport finally gained Olympic status. What followed was the birth of the fiercest rivalry in international sports: Canada vs. USA.

1. 1998 Nagano: The American Upset

The world expected Canada to win the inaugural Gold. They had won every World Championship leading up to the Games. But in the final, the United States flipped the script. Led by captain Cammi Granato and goaltender Sarah Tueting, the Americans won 3–1.

- The Impact: That loss devastated the Canadian program but lit a fire under it. It also inspired a generation of American girls (including future stars like Hilary Knight) who watched Granato on a Wheaties box and realized hockey wasn’t just for boys.

2. 2002 & 2006: The Empire Strikes Back

Stung by the ’98 loss, Canada rebuilt its program with a focus on ruthless conditioning.

- 2002 Salt Lake City: In a game marred by officiating controversies (the referee called 13 penalties against Canada), the Canadians held on to win 3–2. This game cemented Hayley Wickenheiser as the “Gretzky” of women’s hockey—a player so dominant physically and mentally that opponents had no answer for her.

- 2006 Turin: This tournament offered a shock twist. For the first time, the final wasn’t Canada vs. USA. Sweden pulled off a historic upset in the semi-finals, beating the Americans in a shootout. Canada then dismantled the exhausted Swedes 4–1 in the final.

3. 2010 Vancouver: The Party on Ice

Playing on home soil, the Canadian women were unstoppable, outscoring opponents 48–2 throughout the tournament. They shut out the USA 2–0 in the final.

- The Aftermath: The victory is famous for the celebration. Still in full uniform, the Canadian players returned to the ice hours after the fans had left to smoke cigars and drink beer. While the IOC grumbled about “decorum,” the images became iconic symbols of the team’s swagger.

4. 2014 Sochi: The “Golden Comeback”

This is widely considered the greatest game in the history of women’s hockey.

- The Situation: With just 3:26 left in the Gold Medal game, the USA led Canada 2–0. The Americans were seemingly minutes away from ending Canada’s dynasty.

- The Miracle: Canada scored to make it 2–1. Then, with the Canadian net empty, an American clearing attempt hit the post and stayed out—a game of literal inches.

- The Hero: With 55 seconds left, Marie-Philip Poulin tied the game. In overtime, with the US on a power play, Poulin scored again on a sudden-death breakaway. The comeback solidified Poulin’s nickname as “Captain Clutch” and broke American hearts in a way that fueled the rivalry for another decade.

The Legacy of this Era: Between 1998 and 2014, these two nations were so far ahead of the rest of the world that the IOC briefly threatened to remove women’s hockey from the Olympics if other countries didn’t catch up. This pressure forced nations like Finland, Sweden, and Switzerland to invest heavily in their programs, slowly closing the gap and creating the more competitive landscape we see today.

Final Thoughts

The era from 1992 to 2014 was the golden age for fans. We got to see the absolute best players in the world trade their corporate NHL logos for national flags. It legitimized the Olympic tournament as the pinnacle of the sport.

While the “Amateur Era” had its charm and the “Soviet Era” had its mystery, the “NHL Era” had the raw skill. Watching Crosby, Ovechkin, Lidstrom, and Selanne on the same ice wasn’t just a game; it was a celebration of how far the sport had come globally. I greatly hope the return of the NHL to the 2026 Olympics kicks off a new era that can live up to the glory of this one.

Did you miss the original articles kicking off my ‘Olympic Hockey Era’ series ? Don’t worry, you can find them all here:

Hockey’s Olympic History: Tracking Olympic Hockey From 1920 to Current Day

Part I: The Great Inception – When Ice Hockey Was an Olympic Summer Sport (1920–1924)

Part II: The Era of Canadian Olympic Dominance (1928–1952)

Part III: The Red Machine – The Soviet Dynasty & The “Amateur” Lie (1956–1988)

FAQs: The Modern Era

Q: Why was Eric Lindros the captain in 1992 if he wasn’t in the NHL? A: Lindros was a phenomenon. He had been drafted #1 overall in 1991 by the Quebec Nordiques but refused to play for them. While holding out for a trade, he spent the year playing for the Canadian National Team, keeping his amateur status and captaining the Olympic squad.

Q: Why did Gretzky get benched in the 1998 shootout? A: Coach Marc Crawford believed that Ray Bourque, a defenseman known for his accuracy, was a better statistical choice for a specific shot. He also felt Gretzky’s “move” (usually a slap shot) wasn’t suited for a shootout against Hasek. It is a decision Crawford has been criticized for every day since.

Q: What is the “Unified Team” (1992)? A: After the USSR collapsed in December 1991, the former Soviet states (Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, etc.) agreed to compete together one last time in Albertville 1992 to keep their rosters intact. They competed under the Olympic flag.

Q: Why did the NHL stop going to the Olympics after 2014? A: Money and risk. NHL owners hated pausing the season for two weeks (losing revenue) and risking injury to their multi-million dollar stars (e.g., John Tavares suffered a season-ending injury in 2014). The NHL skipped 2018 and 2022, though they have agreed to return for 2026.

Q: Who has the most Olympic points in this era? A: Teemu Selanne (Finland). The “Finnish Flash” played in 6 Olympics (from 1992 to 2014) and is the all-time leading scorer in Olympic hockey history with 43 points.