Part II: The Era of Canadian Olympic Dominance (1928–1952)

Part II of my ‘Olympic Hockey Era’ series continues directly from Part I of the series, the Great Inception, as Canadian ice hockey players further assert their dominance in the world.

If the early 1920s were the “origin story” of Olympic hockey, the period from 1928 to 1952 is the “Canadian Era.” I’m fascinated by this stretch of history because it represents a model of sports that simply doesn’t exist anymore.

Today, we obsess over “Dream Teams.” We want the absolute best individual players from every corner of the country to form a super-squad. But back then? Canada didn’t send an all-star team. They sent a club.

Canada sent university students, World War II airmen, and car dealership employees to defend the nation’s honor.

I love digging into this era because beneath the surface of gold medals, the cracks were already forming for Canada. The world was catching up, the politics were getting ugly (i.e. 1936), and the definition of “amateur” was becoming a battleground. This is the story of how a dynasty held on—until it couldn’t.

Table of Contents

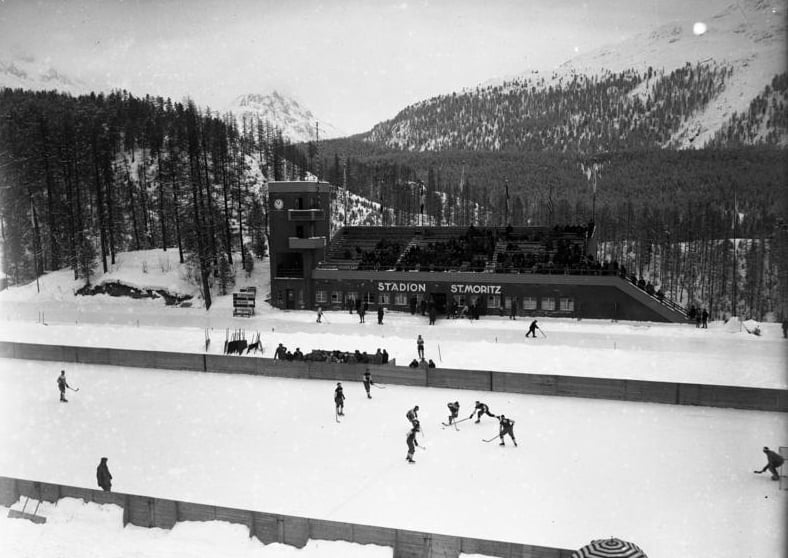

I. 1928 St. Moritz: The “Super-Bye”

Dates: Feb 11–19, 1928

Venue: Badrutts Park (St. Moritz, Switzerland)

By 1928, the world had accepted a harsh reality: Canada wasn’t just better at hockey; they were playing a different sport entirely. The gap in skill was so terrifyingly vast that tournament officials made a decision that remains unique in Olympic history. They created a “Super-Bye.”

While 10 other nations—including Sweden, Switzerland, and Great Britain—had to slog through a grueling preliminary round to prove their worth, Canada was given a free pass directly to the final medal round. They sat in the Swiss Alps for a week, watching the other teams exhaust themselves, simply waiting for a challenger to emerge.

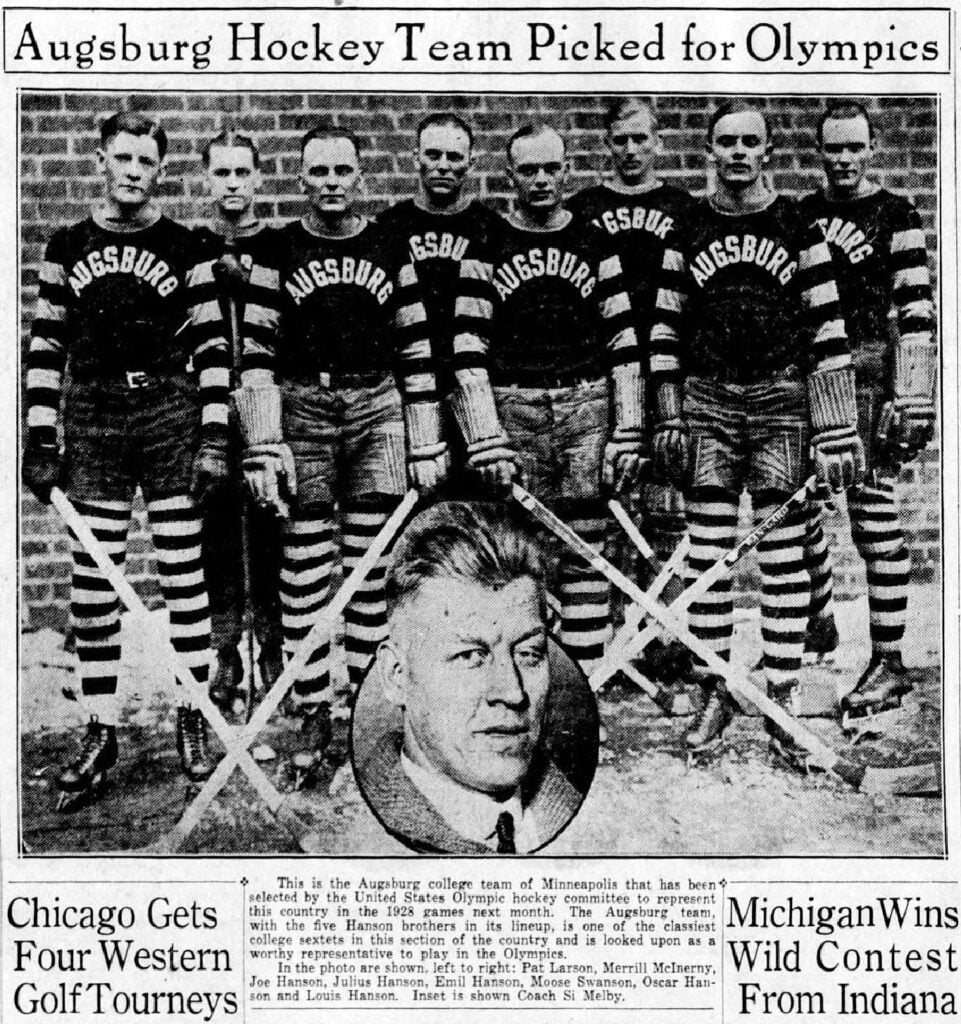

Sidebar: Why Was There No Team USA?

The United States’ absence in 1928 wasn’t just a scheduling conflict—it was a bureaucratic disaster. Following the collapse of their governing body (the USAHA) in 1926, the American Olympic Committee scrambled to find a team to represent the nation.

They approached elite schools like Harvard, Yale, and the University of Minnesota, but all declined due to lack of funding or refusal to let students miss class. Finally, a small school in Minneapolis—Augsburg College—stepped up. They accepted the bid and even offered to pay half their own way.

However, the Chairman of the American Olympic Committee, General Douglas MacArthur, personally intervened. He rejected Augsburg’s bid, claiming the team—which was led by five brothers named Hanson—was “not representative of American hockey” because the players were considered too culturally “Canadian” (despite being American-born). As a result of MacArthur’s decision, the USA stayed home, marking the only time in history they have failed to field an Olympic hockey team.

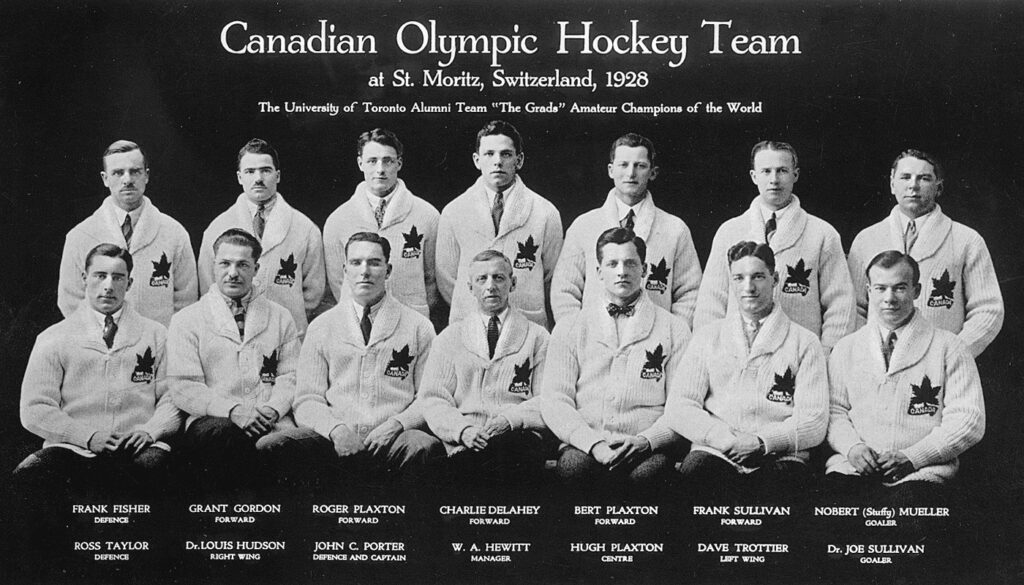

The Team: The University of Toronto Grads Unlike the rough-and-tumble war veterans of 1920 or the blue-collar Granites of 1924, the 1928 team was composed of cerebral, elite athletes. The U of T Grads were initially coached by Conn Smythe (the man who would later build Maple Leaf Gardens), though he refused to go to Switzerland due to a fierce dispute with the team regarding player selection. In his absence, the team was led by Dr. Joseph Sullivan, a medical intern who also happened to be the goaltender.

The Performance: When Canada finally took the ice, the “mercy” of the bye proved unnecessary. They played three games in the medal round and turned them into a clinic on defensive suffocation.

- Canada 11 – Sweden 0

- Canada 14 – Great Britain 0

- Canada 13 – Switzerland 0

The Stat Line: The Grads outscored the best teams in the world 38–0. Goaltender Joseph Sullivan played every minute of the tournament and did not allow a single puck to cross his goal line. It stands as perhaps the most mathematically perfect performance in the history of international sports.

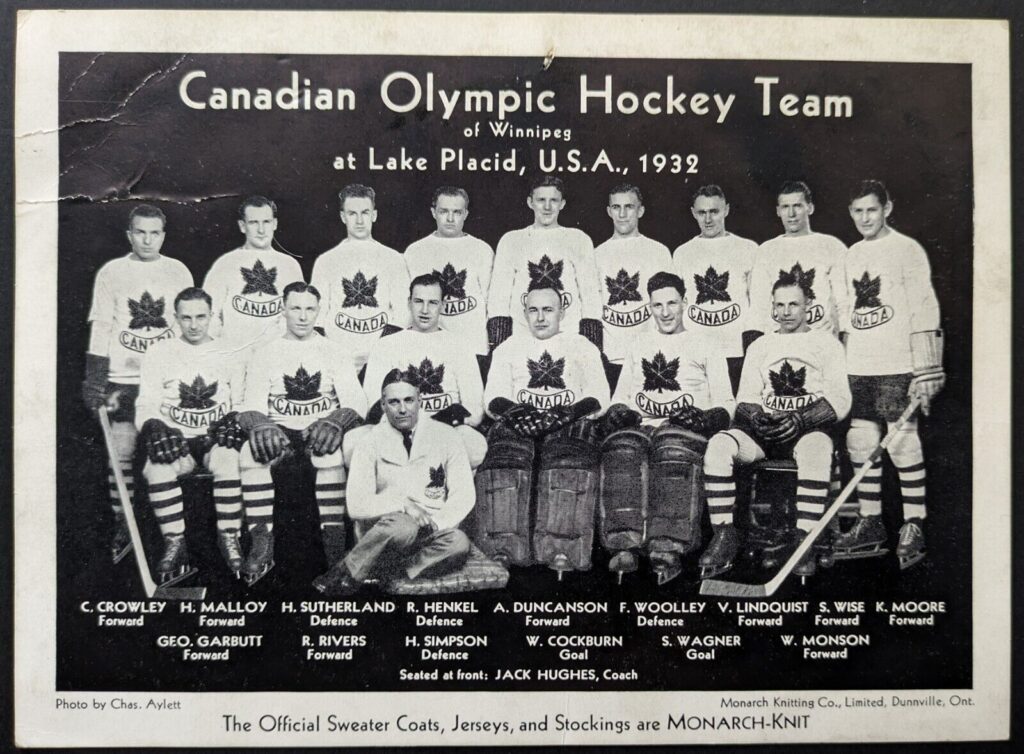

II. 1932 Lake Placid: The Depression Games

Dates: Feb 4–15, 1932

Venue: Jack Shea Arena (Lake Placid, New York)

Four years later, the mood had shifted from triumph to survival. The Great Depression had decimated the global economy. Crossing the Atlantic was a luxury few nations could afford, and as a result, the 1932 Olympic hockey tournament featured only four teams: Canada, the United States, Germany, and Poland.

The Team: The Winnipeg Hockey Club Canada sent the Winnipeg Hockey Club to upstate New York. While talented, they lacked the overwhelming firepower of previous entries. The tournament format was a double round-robin, meaning every team played every other team twice.

The Warning Shot: For the first time in Olympic history, Canada looked mortal. The Americans, playing on home soil and fueled by a rowdy crowd, refused to be intimidated.

- Game 1: In their first meeting, the US dragged Canada into overtime. Canada scraped out a 2–1 victory, but the aura of invincibility was shattered.

- Game 2: In the rematch, the Americans matched Canada stride for stride, ending in a 2–2 tie.

Although Canada secured the Gold Medal based on points, the 1932 Games were a pivotal turning point. They proved that the gap was closing. The Americans had shown the world that the “machine” could be jammed, provided you had enough grit and a hot goaltender.

III. 1936 Garmisch-Partenkirchen: The “Great Theft”

Dates: Feb 6–16, 1936

Venue: Olympia-Kunsteisstadion (Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Nazi Germany)

If 1932 was a warning, 1936 was the revolution. Held in the shadow of the rising Nazi regime, this tournament provided the biggest controversy in early hockey history and Canada’s first-ever Olympic defeat.

The Controversy: The “Imported” British Great Britain arrived with a team that looked suspicious to everyone in the Canadian camp. The British roster was stacked with players like Jimmy Foster and Alex Archer—men who spoke with Canadian accents, learned to play on Canadian rinks, and had only recently moved to the UK. They were “dual citizens,” holding British passports by birthright, but culturally and athletically, they were Canadian exports. Canada filed a formal protest, labeling them “imported mercenaries,” but the IIHF ruled them eligible.

The Trap: The tournament format was a disaster waiting to happen.

- Canada and Great Britain met in the semi-final round. In a shocking defensive battle, Great Britain won 2–1, with Jimmy Foster (the “British” goalie who normally played in Winnipeg) standing on his head.

- Canada assumed this was just a hurdle. They expected to crush their remaining opponents and meet Britain again in the Final to settle the score.

- However, the rules stated that results against medal-round opponents carried over. Because Canada had already lost to Britain in the semi-finals, they were not given a rematch. Britain simply had to tie their remaining games to secure Gold.

The Aftermath: Canada was apoplectic. They felt they had been robbed by their own citizens and a bureaucratic loophole. They boycotted the post-game banquet, leaving the British team (and the Nazi officials) to celebrate alone. It remains the only Olympic Gold Medal in British hockey history, forever with an asterisk in the minds of Canadian purists.

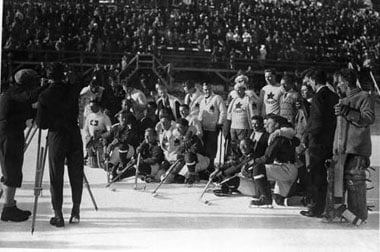

IV. 1948 St. Moritz: The “Two US Teams” Fiasco

Dates: Jan 30 – Feb 8, 1948

Venue: St. Moritz Olympic Ice Rink (St. Moritz, Switzerland)

The Olympics returned after a 12-year hiatus caused by World War II, but the peace did not extend to the ice. The 1948 tournament is remembered less for the hockey and more for a political civil war that nearly cancelled the event.

The Civil War: Two rival governing bodies in the United States hated each other so much they both sent full teams to Switzerland:

- The AHAUS Team: Supported by the IIHF. They were talented but accused of being “commercial” players (receiving small stipends), violating the strict amateur code.

- The AAU Team: Supported by the US Olympic Committee and Avery Brundage. They were “pure” amateurs (mostly college kids) but significantly less talented.

The Compromise: The dispute turned into a farce. At the Opening Ceremony, the AAU team marched in the parade, while the AHAUS team watched from the stands. But when the puck dropped, the AHAUS team was the one allowed to play. The IOC, fed up with the bickering, ruled that the US team was “unofficial.” Their games would not count in the standings, and they were ineligible for a medal, no matter how well they played.

The RCAF Flyers: Amidst this chaos, Canada sent a team that perfectly encapsulated the post-war era: the RCAF Flyers. They were active-duty Royal Canadian Air Force personnel, many of whom had served in WWII. They weren’t an elite club; they were a patchwork squad assembled weeks before the Games. Yet, they played with a military discipline.

Led by goaltender Murray Dowey (who pioneered a catching glove that looked like a first baseman’s mitt), they shut out 5 of their 8 opponents. In a decisive final game against the Swiss, playing on slushy, sun-melted ice, they won 3–0 to reclaim the Gold and restore national pride.

V. 1952 Oslo: The End of the Line

Dates: Feb 15–25, 1952

Venue: Jordal Amfi (Oslo, Norway)

By 1952, Canada was running on fumes. The world had recovered from the war, and European hockey programs were becoming sophisticated. Canada was represented by the Edmonton Mercurys, a team sponsored by a local car dealership.

The Last Stand: The Mercurys were a gritty, workmanlike team, but they lacked the dominance of the 1920s. They struggled to put teams away. In a pivotal game against the USA, they blew a lead and settled for a 3–3 tie. They eventually won Gold, but it was a math problem, not a coronation—they finished just one point ahead of the Americans in the round-robin standings.

– Oslo, Norway.

The Significance: When the Mercurys stood on the podium in Oslo, listening to “God Save the Queen” (Canada’s anthem at the time), no one knew they were witnessing a funeral for an era.

- The Soviet Shadow: Sitting in the stands, scribbling notes in pads, were coaches from the Soviet Union. They were studying the Canadian game, dissecting its weaknesses, and preparing to launch their own state-sponsored “Red Machine.”

- The Drought: Canada would not win another Olympic Gold for 50 years. The age of the car salesman, the student, and the airman defeating the world was over. The age of the “shamateur” professional was about to begin.

Final Thoughts

Looking back at the “Canadian Era,” I’m struck by how fragile it actually was. We tend to view Canada’s early dominance as inevitable, but when you look closely, you see the cracks: the “British” team stealing gold in ’36, the near-misses against the USA, and the reliance on car salesmen and students to fight national battles.

By 1952, the world had changed. The “gentleman’s game” of the Victorian era was gone. The Cold War had started, and sport was about to become a proxy for geopolitical dominance. The Edmonton Mercurys walked off the ice in Oslo as champions, but they were the last of their kind. The Red Machine was coming.

Did you miss my original article kicking off the ‘Olympic Hockey Era’ series or want to take a deeper dive into Part I, the 1920-1924 inception era of ice hockey in the Winter Olympics? Don’t worry, I have you covered:

Hockey’s Olympic History: Tracking Olympic Hockey From 1920 to Current Day

The Great Inception: When Ice Hockey Was an Olympic Summer Sport (1920–1924)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): The Canadian Era

Q: Why did Canada send club teams instead of a National Team? A: In this era, there was no centralized “Hockey Canada” organization to select an all-star team. It was also a logistical nightmare to gather players from across a massive country for a training camp in the middle of winter. It was easier (and cheaper) to simply send the winner of the Allan Cup (the senior amateur championship) since they already had chemistry and a coach.

Q: Was the 1936 Great Britain team technically cheating? A: Technically? No. Ethically? Maybe. The rules regarding citizenship were loose. The players held valid British passports because they were born in the UK or had British parents, even if they had lived in Canada their whole lives. After 1936, the IIHF tightened the rules to require players to actually live in the country they represented for a set period.

Q: Did World War II impact the rosters? A: Massively. The 1940 and 1944 Olympics were cancelled. By 1948, many of the best young athletes in the world had been killed in combat or had lost their prime developmental years to military service. The 1948 RCAF Flyers were literally a military team—men who had transitioned from fighting in the air to fighting on the ice.

Q: Why did it take 50 years for Canada to win again after 1952? A: Two words: Soviet Union. Starting in 1956, the USSR entered the Olympics with “state amateurs”—players who trained full-time like professionals but were listed as soldiers or workers to skirt Olympic rules. Canada, still sending true amateurs (and barred from using NHL players), simply couldn’t compete with the Soviet machine until the rules changed in the late 1990s.