Hockey’s Olympic History: Tracking Olympic Hockey From 1920 to Current Day

The 2026 Milano Cortina Olympics are shaping up to be the most significant hockey tournament in over a decade. Analysts are calling it the “Ultimate Best-on-Best” because it marks the first time since 2014 that the world’s elite (NHL stars) and the newly professionalized women’s field (PWHL) will compete on the same stage.

I don’t know about you, but after watching the 4 Nations Face-Off during the hockey break of the 2024/25 season, I can’t wait to see what’s in store for another meeting of the best international teams.

I love learning about the history of hockey. Having the additional background context for how the game and players have progressed to where it’s at now makes watching each game so much more exciting. Especially on the international stage.

With that in mind I’ve put together an outline of the history of hockey in the olympics, from it’s induction to the Olympics in 1920, to the highly anticipated and extremely competitive matchups coming up for the 2026 Olympics in Milano, Italy.

This article starts with the history dating back to 1920, but if you want to jump ahead to take a peek at the outlook for the 2026 games feel free to do so in the table of contents.

Alright, let’s jump in!

Table of Contents

I. Hockey’s Olympic Inception (1920–1924)

This era is characterized by the transition of hockey from a “special exhibition” to a standardized Olympic sport. It is also the era of the “club system,” where nations were represented by their best amateur club teams rather than national all-star squads.

A. 1920 Antwerp (The Summer Debut)

- Context: Oddly, ice hockey made its Olympic debut at the Summer Games in Antwerp, Belgium. The matches were played in April at the Palais de Glace d’Anvers.

- The Format (7-Man Hockey): The game looked very different from today. Teams played with seven men on the ice: a goaltender, two defensemen, three forwards, and a “rover” (a position that had already been phased out in the NHL but persisted in amateur rules). The rover had no fixed position and roamed the ice to create offensive advantages.

- The “Bergvall” System: The tournament used a flawed bracket system called the Bergvall System.

- First, a bracket was played to determine the Gold winner.

- Once Gold was decided, all teams that lost to the Gold medalist played a new mini-bracket for Silver.

- Finally, all teams that lost to the Silver medalist played for Bronze.

- Critique: This meant that the second-best team in the world could theoretically be eliminated in the first round if they happened to play the Gold winner early, forcing them to play many extra games to claw back to Silver.

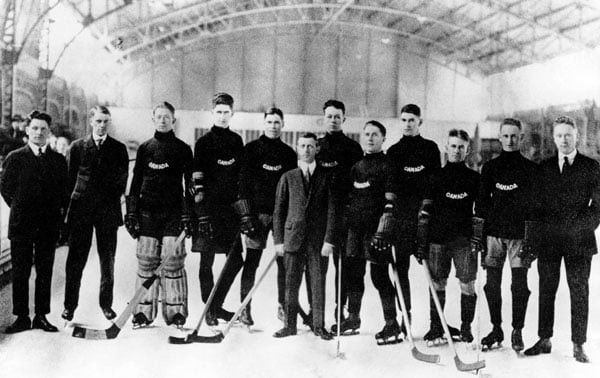

- The Winner: Canada, represented by the Winnipeg Falcons.

- The Falcons were a team of Icelandic-Canadians who had faced significant ethnic prejudice at home. They dominated the tournament, outscoring opponents 29–1.

B. 1924 Chamonix (The Move to Winter)

- Context: The 1924 Games in Chamonix, France, were the first official Winter Olympics (originally styled as a “Winter Sports Week” linked to the Paris Summer Games). Hockey became a permanent winter fixture here.

- Standardization (6-Man Hockey): The rules were modernized to align closer with the NHL (current rules for number of players can be found here). The rover position was eliminated, creating the standard six-man format (1 goalie, 2 defense, 3 forwards) used today. The game was played outdoors on natural ice.

- The Dominator (Harry Watson): The tournament is legendary for the performance of Canadian forward Harry Watson. He scored a staggering 36 goals in just 5 games (including 13 in a single game against Switzerland). That’s mind blowing to think about.

- The Winner: Canada, represented by the Toronto Granites.

- The gap between Canada and the rest of the world was massive. Canada outscored its opponents 110–3 over the course of the tournament.

- The only (somewhat) competitive game was the final against the USA, which Canada won 6–1. This match birthed the trans-continental rivalry that defines the sport today.

Comparison: 1920 vs. 1924

| Feature | 1920 Antwerp (Summer) | 1924 Chamonix (Winter) |

| Players on Ice | 7 (Includes Rover) | 6 (Rover Eliminated) |

| Substitutions | No substitutions (unless injured) | Substitutions allowed |

| Venue | Indoor (Palais de Glace) | Outdoor (Stade Olympique) |

| Periods | 2 periods of 20 mins | 3 periods of 20 mins |

| Canadian Team | Winnipeg Falcons | Toronto Granites |

| Goal Differential | Canada +28 (29–1) | Canada +107 (110–3) |

Want a deeper dive into the 1920-1924 inception era of ice hockey in the Winter Olympics? I have you covered:

The Great Inception: When Ice Hockey Was an Olympic Summer Sport (1920–1924)

II. The Era of Canadian Dominance (1928–1952)

This period is defined by Canada’s near-total control of the sport, usually represented by senior amateur club teams rather than national all-star squads. However, it also marks the beginning of political controversies and eligibility disputes that would plague the Olympics for decades.

A. 1928 St. Moritz: The “Super-Bye”

- The Team: Canada was represented by the University of Toronto Graduates, while USA was unable to put together a team. Being the only time in hockey Olympic history they missed the games.

- The Dominance: The gap between Canada and the rest of the world was so vast that officials decided it was unfair to make them play in the preliminary rounds. Canada was given a bye directly to the final medal round—a unique occurrence in Olympic history.

- The Result: Canada played only three games, winning all of them and outscoring opponents 38–0.

B. 1932 Lake Placid: The Depression Games

- Context: Due to the Great Depression, only four nations could afford to send teams to Lake Placid, New York (Canada, USA, Germany, Poland).

- The Result: It was a double round-robin. Canada (represented by the Winnipeg Hockey Club) won Gold, but the Americans proved the gap was closing. The USA managed a 2–2 tie in one game and lost the other by only a single goal (2–1).

C. 1936 Garmisch-Partenkirchen: The “British” Upset

- The Controversy: Great Britain won their first and only Olympic Gold in ice hockey, shocking the world. However, the British roster was controversial; it was composed almost entirely of British-Canadian dual citizens—players who had grown up learning the game in Canada but held British birthrights. Canada protested, calling them “imported” players, but the IIHF allowed them to play.

- The Formatting Blunder: Canada lost to Great Britain 2–1 in the semi-finals. Under the rules of that specific tournament, results against medal-round opponents carried over to the final round. Canada assumed they would get a rematch against GB in the finals to fight for Gold, but they did not. The carry-over loss doomed them to Silver.

D. 1948 St. Moritz: The “Two US Teams” Fiasco

- The Conflict: This is arguably the biggest administrative mess in Olympic hockey history. Two rival bodies in the United States both sent teams to Switzerland:

- The AHAUS Team: Supported by the IIHF, but contained “commercial” players (paid small stipends).

- The AAU Team: Supported by the US Olympic Committee and Avery Brundage, consisting of “pure” amateurs (mostly college students).

- The Resolution: The dispute threatened to cancel the tournament. A bizarre compromise was reached: The AAU team marched in the Opening Ceremony but was not allowed to play. The AHAUS team played the games, but the IOC ruled their games “unofficial,” meaning they could not win a medal regardless of their record.

- The Winner: Canada (represented by the RCAF Flyers, a team of Royal Canadian Air Force personnel) took Gold on goal differential.

E. 1952 Oslo: The End of an Era

- The Last Gold: In the 1952 Winter Olympics in Oslo, Norway, Canada was represented by the Edmonton Mercurys, who had won the world ice hockey championship in 1950. The Mercs won the first three games with a combined score of 39–4 but had a more difficult time against the Czechoslovakian (4–1) and Swedish (3–2) teams. Canada won all seven of its games before facing the United States. A 3–3 tie with the Americans (who had lost to Sweden) was good enough for gold. The Canadians would not win hockey Olympic gold again for 50 years (until 2002).

- The Shift: The Soviet Union (USSR) was observing these games and preparing to enter in 1956. The age of amateur club teams dominating the world was effectively over.

Women’s Hockey: The “Missing” Era

While men competed for Gold, women were completely barred from Olympic hockey. However, this was ironically the era of the greatest women’s team in history, proving that the talent existed even if the platform did not.

- The Preston Rivulettes (1931–1940):

- Originating from Preston, Ontario, this women’s team is statistically one of the most dominant in the history of all sports.

- The Record: They played an estimated 350 games over a decade and lost only two times.

- The Barrier: Despite their dominance, there was no World Championship or Olympic pathway for them. Women’s hockey was often dismissed by officials as a “health risk” or “too rough” for ladies.

- The Decline: When WWII began, the team disbanded, and women’s hockey entered a “Dark Age” where participation plummeted for decades, not recovering until the 1980s.

III. The Soviet Dynasty & “Amateurism” (1956–1988)

This era is defined by the Cold War and the ideological battle between East and West. On the ice, it saw the rise of the most disciplined team in history: the Soviet “Red Machine.”

A. The Rise of the Soviet “State Amateurs”

- The Entry (1956): The Soviet Union (USSR) entered their first Winter Olympics in Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy and immediately won Gold, ending the era of Canadian dominance.

- The “Shamateur” Controversy: The Olympics strictly forbade professional athletes (specifically NHL players). However, the Soviets utilized a loophole: their players were technically “soldiers” in the Red Army or “workers” in aircraft factories, making them “amateurs” on paper. In reality, they lived in barracks and trained as full-time professionals 11 months a year.

- The Style: Under coaches like Anatoly Tarasov and Viktor Tikhonov, the Soviets pioneered a style of play based on “interchangeability” and creative, short passing rather than the North American “dump and chase” method.

B. American Exceptions: 1960 and 1980

While the USSR won every other Gold from 1956 to 1992, the United States managed two historic upsets on home soil:

- 1960 Squaw Valley: The “Forgotten Miracle.” Led by the Christian brothers and Bill Cleary, the US defeated the Soviets and Canadians to win their first Gold.

- 1980 Lake Placid (The “Miracle on Ice”): Against the backdrop of the Iranian Hostage Crisis and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, a team of US college students defeated the defending 4-time Gold medalist Soviet team.

- Significance: This is widely considered the greatest upset in sports history. The US went on to beat Finland in the final to secure Gold.

Women’s Hockey: The Slow Rebirth (1956–1988)

During the peak of the Cold War, women’s hockey was almost entirely absent from the public eye, but the foundation for its eventual Olympic inclusion was quietly being built in the 1960s and 70s.

- The Collegiate Revival (1960s): After the “Dark Age” following WWII, women’s hockey began to resurface at the university level. In 1961, the first intercollegiate women’s league was formed in Ontario, Canada.

- The Growth in the US (1970s): Title IX (1972) in the United States mandated equal opportunity in education and sports, which eventually provided the funding and infrastructure for women’s varsity hockey programs at American universities.

- The First “Unsanctioned” World Tournament (1987): * While still not an Olympic sport, the Ontario Women’s Hockey Association (OWHA) organized the first World Invitational Tournament in 1987.

- Delegates from participating countries used this event to lobby the IIHF (International Ice Hockey Federation) for an official World Championship, which was finally granted in 1990.

- The Olympic Catalyst: The success of the 1990 Women’s World Championship in Ottawa (where over 9,000 fans attended the final) proved to the IOC that women’s hockey was commercially viable and competitively ready.

IV. The Modern Era & NHL Expansion (1998–2014)

This era represents the “best-on-best” golden age. It was a transformative period where the Olympics finally showcased the highest level of talent on the planet for both men and women.

A. The Men’s Game: The NHL Era Begins (1998)

- The Policy Shift: In 1995, the NHL, the NHL Players’ Association (NHLPA), and the IIHF reached a landmark agreement to allow NHL players to participate. The league agreed to shut down for two weeks mid-season to accommodate the Games.

- 1998 Nagano (The “Dream Tournament”): * Hosted in Nagano, Japan, expectations for the 1998 Winter Olympics were high for Canada and the USA, but to everyone’s surprise, the Czech Republic pulled off a historic upset to win Gold.

- Dominik Hašek (The Dominator) delivered arguably the greatest goaltending performance in history, shutting out Russia 1–0 in the final and stopping all five Canadian shooters in a legendary semifinal shootout.

- 2002–2014 Highlights:

- 2002 Salt Lake City: Canada won its first Gold in 50 years, defeating the USA 5–2.

- 2010 Vancouver: Perhaps the most famous goal in history—Sidney Crosby’s “Golden Goal”—gave Canada the win over the USA in overtime on home soil.

- 2014 Sochi: The last tournament of this era featuring NHL players before a 12-year hiatus. Canada dominated, allowing only 3 goals in 6 games.

B. Women’s Hockey: The Olympic Debut (1998)

- The Long-Awaited Debut: Women’s ice hockey officially became an Olympic sport at the 1998 Nagano Games in Japan. It featured 6 teams: USA, Canada, Finland, China, Sweden, and Japan.

- The Inaugural Gold (1998):

- While Canada had won every World Championship leading up to 1998, the United States won the first-ever Olympic Gold, defeating Canada 3–1 in the final.

- This win had a massive cultural impact in the US, similar to the 1999 Women’s World Cup in soccer, leading to a 300% increase in girls’ hockey registration over the following decade.

- The Canadian Dynasty (2002–2014):

- Following the 1998 loss, Canada went on a tear, winning four consecutive Gold medals.

- 2014 Sochi Final: This is considered one of the greatest hockey games ever. Canada trailed the USA 2–0 with less than four minutes left. They scored two quick goals to force overtime, where Marie-Philip Poulin (often called “Captain Clutch”) scored the winner.

- Key Figure: Marie-Philip Poulin (Canada)

- During this era, Poulin established herself as the ultimate big-game player. She is the only hockey player (male or female) to score goals in four different Olympic gold medal games (2010, 2014, 2018, 2022).

Impact and Progress Table (1998–2014)

| Feature | Men’s Tournament | Women’s Tournament |

| Star Power | NHL Legends (Wayne Gretzky, Sid Crosby, Jaromir Jagr) | Icons (Marie-Philip Poulin, Cammi Granato, Hayley Wickenheiser) |

| Key Rivalry | Canada vs. USA / Russia / Sweden | Canada vs. USA (The “Big Two”) |

| Growth Metric | Global TV ratings peaked (2010 Final) | Participation tripled in North America |

| Format | NHL-sized rinks (2002, 2010) vs Olympic | Played exclusively on Olympic-size ice |

V. Recent Volatility & The Path to 2026 (2018–Present)

The current era is defined by a “return to roots” for the men’s game due to outside forces, while the women’s game has seen historic growth and the birth of a new professional infrastructure.

A. The Men’s Game: The NHL Hiatus (2018–2022)

- The 2018 PyeongChang Absence: After five consecutive Olympics, the NHL declined to participate in 2018. The league cited concerns over travel costs, insurance, and the lack of a “meaningful market” in South Korea to justify a mid-season shutdown.

- The Winner: The Olympic Athletes from Russia (OAR) won gold in a thrilling 4–3 overtime victory against a surprising German team.

- The 2022 Beijing Pivot: NHL players were originally scheduled to return for Beijing. However, a massive surge in COVID-19 cases in late 2021 forced the league to postpone dozens of games. The NHL used the “Olympic break” to make up those games instead.

- The Winner: Finland won its first-ever Olympic gold medal in ice hockey, defeating the Russian Olympic Committee (ROC) 2–1. Slovakia also made history by winning its first-ever hockey medal (Bronze), led by 17-year-old phenom Juraj Slafkovský.

B. Women’s Hockey: The Rivalry & Professionalization

- 2018 PyeongChang (The Shootout): In one of the most iconic moments in women’s sports, the United States ended Canada’s 20-year gold medal streak. The game went to a shootout, where Jocelyne Lamoureux-Davidson scored a triple-deke winner and goalie Maddie Rooney made a historic final save.

- 2022 Beijing (The Record-Breakers): Canada reclaimed gold with a 3–2 win. This tournament was notable for the statistical dominance of Sarah Nurse, who set an Olympic record for most points (18) and assists (13) in a single tournament.

- The PWHL Era (2024–Present): For the first time, women’s Olympic hockey is now supported by a stable, unified professional league—the Professional Women’s Hockey League (PWHL). This means players are now training and playing at a professional level year-round, which is expected to drastically increase the depth of international competition beyond just the “Big Two” (Canada/USA).

C. The Future: 2026 Milano Cortina & 2030

- The Best-on-Best Return: In February 2024, the NHL, NHLPA, and IIHF officially finalized an agreement for NHL players to return for the 2026 and 2030 Olympics.

- The “McDavid Era”: 2026 will mark the first time superstars like Connor McDavid (Canada), Nathan MacKinnon (Canada), Cale Makar (Canada), Zach Eichel (USA), Auston Matthews (USA), and Leon Draisaitl (Germany) will compete in the Olympics. It will also be Sidney Crosby’s first Olympics back since winning gold in 2010 and 2014.

- Rink Standardization: While the 2026 Games will be played in Milan, the rinks will officially use NHL-sized dimensions, moving away from the wider international ice that has been the Olympic standard for a century.

Era Summary Table

| Olympics | Men’s Gold | Women’s Gold | Major Shift |

| 2018 | OAR (Russia) | USA | NHL absence; Women’s rivalry peaks |

| 2022 | Finland | Canada | COVID-19 disruption; First Gold for Finland |

| 2026 | TBD | TBD | NHL Return; PWHL professional era |

As mentioned at the start, the 2026 Milano Cortina Olympics are shaping up to be the most significant hockey tournament in over a decade.

How the 2026 Winter Olympics are shaping up so far

I. Men’s Tournament: The Powerhouses Return

For the first time ever, we will see a generation of “best-in-world” players who have never had an Olympic opportunity (McDavid, Matthews, Makar).

- The Favorites: Canada: The consensus favorite (by a small margin). This is largely due to their historic depth and recent win at the 4 Nations Face-Off (a 2025 preview tournament) as proof of their dominance. Although, USA won their first match up earlier in the tourney.

- USA: Right on Canada’s heels. While Canada has the best individual stars, the US has the best goaltending depth in history and a younger, faster defensive core and clearly held their own in the 4 Nations tournament.

- The Standout Players:

- Connor McDavid (CAN): Arguably the best player in the world. This is his first Olympic chance at age 29 (by the time the Olympics start); he easily will be one of the tournament’s focal points.

- Nathan MacKinnon (CAN): Also, arguably the best player in the world and also on Team Canada. He’s a threat from anywhere on the ice and will be a menace for any nation that has to go up against him.

- Auston Matthews (USA): The premier goal-scorer of the era. He leads a US team that finally believes they can surpass Canada in a “best-on-best” format. Although, recently Matthews has slowed down on the scoring/points front, putting his value to the team in question.

- Zach Eichel (USA): Currently playing for the Vegas Golden Knights, Eichel has consistenly been one of the top players in the NHL. It’s possible he will take a bigger role and could even earn captain for USA as he was a pivotal player in the 4 Nations Face-off tourney.

- Connor Hellebuyck / Jake Oettinger (USA): The US goaltending is considered a “juggernaut.” Their ability to steal a game is higher than Canada’s current goaltending options.

There’s so many other great players between Canada and USA alone. It’s difficult to cover them all.

II. Women’s Tournament: A New Hierarchy?

While the Canada-USA rivalry remains the centerpiece, the landscape has shifted because players now compete in the PWHL, leading to higher year-round intensity.

- The Favorites:

- USA: Surprisingly, many analysts currently favor the US over Canada. This is due to a dominant 2025 “Rivalry Series” sweep where the Americans looked faster and more cohesive under pressure.

- Canada: Never an underdog for long. Analysts warn against betting against “Captain Clutch” (Marie-Philip Poulin), though they note Canada is currently in a “youth transition” phase.

- The Standout Players:

- Marie-Philip Poulin (CAN): Looking to win her fourth Gold. Analysts are watching to see if she can break the all-time Olympic goal record held by Hayley Wickenheiser.

- Taylor Heise (USA): The 2023 PWHL first-overall pick. Experts see her as the “new face” of the US team—a fast, creative center who can break Canada’s defensive structure.

- Sarah Fillier (CAN): After a standout rookie Olympic performance in 2022, she is now expected to take over the primary scoring mantle from the older veterans.

III. Analyst “Wildcards” & Notes

- The “Swiss Value”: Some analysts are calling Switzerland the best “value bet” for a medal. They recently reached the World Championship final and possess elite NHL talent like Roman Josi and Nico Hischier.

- No Russia: The ban on Russia playing in international hockey tournaments remains intact, meaning the results of the 2026 Olympics will forever be questioned as Russia has several talented players that could very well make a silver or gold medal run.

- Rink Dimensions: Interestingly, the 2026 rinks will be roughly three feet shorter than a standard NHL rink. This will lead to a more physical, “tight” style of play that favors the North American teams over the typically more “flowy” European teams.

- The Goalie Gap: The biggest talking point among analysts is Canada’s “weakness” in net compared to the USA (Hellebuyck/Swayman) and Sweden (Ullmark/Markström). If Canada loses, it will likely be because of a goaltending duel.

That’s everything for now! Hope you found my historical breakdown and outlook for the upcoming olympics useful. If you still want to get more information on how each international team stacks up then please check out my guide on the best international teams.

2025 International Hockey Overview – Which Countries Are the Best at Ice Hockey?