Part I: The Great Inception – When Ice Hockey Was an Olympic Summer Sport (1920–1924)

The inception of ice hockey into the “winter” olympics is truly a fascinating one. I have always been drawn to the “origin stories” of sports—those messy, chaotic early days before the rules were polished and the stadiums were built. There is something incredibly grounding about peeling back the layers of history to find that the sleek, high-tech game we watch today started in a completely different universe.

To me, the inception of Olympic hockey (1920–1924) is the ultimate rabbit hole. I love this era because it feels like the “Wild West.” It was a time when hockey wasn’t even a Winter Olympic sport yet, when “rovers” still patrolled the ice, and when the players weren’t millionaires, but soldiers returning from the trenches of the Great War. It’s gritty, it’s weird, and it’s surprisingly emotional.

When I dig into the stories of the Winnipeg Falcons or Harry Watson, I’m not just reading box scores; I’m seeing the DNA of the sport being written in real-time. If you want to understand why hockey is the way it is today, you have to start here—in the spring of 1920, on a cramped rink in Belgium, where a group of outcasts changed everything.

As mentioned in my original “Olympic Hockey Era’ post, Tracking Olympic Hockey From 1920 to Current Day, this era isn’t just about Canada winning; it’s about the chaotic, experimental birth of the international game.

Here’s a quick snapshot of the time era:

| Feature | 1920 Antwerp | 1924 Chamonix |

| Context | Summer Games side-event | First Official Winter Games |

| Players on Ice | 7 (Rover included) | 6 (Rover removed) |

| Ice Surface | Indoor (Small: 56m x 18m) | Outdoor (Natural Ice) |

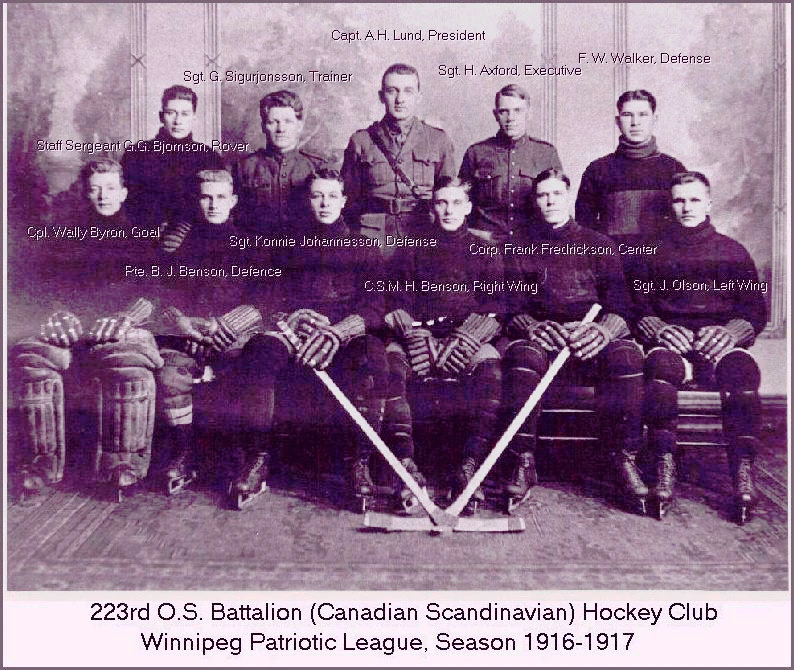

| Top Scorer | Frank Fredrickson (12 goals) | Harry Watson (36 goals) |

| Legacy | The “Icelandic” Victory | The “Unbeatable” Standard |

Table of Contents

I. 1920 Antwerp: The “Summer” Anomaly

Dates: April 23–29, 1920

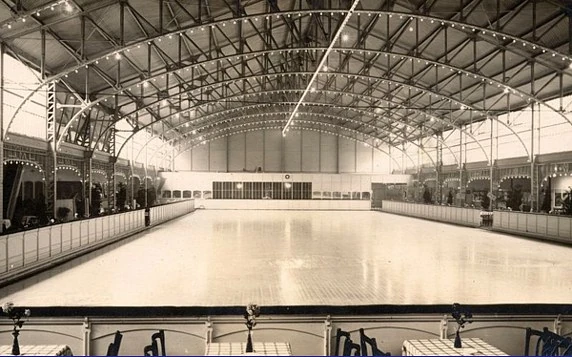

Venue: Palais de Glace d’Anvers (Antwerp, Belgium)

It remains one of the best trivia questions in sports history: “When was the first Olympic hockey gold medal awarded?” The answer is the 1920 Summer Games.

Because the concept of a “Winter Olympics” did not yet exist, organizers squeezed ice hockey (along with figure skating) into the Summer program. The matches were played in late April, weeks before the track and field events began.

The Venue: The games were held at the Palais de Glace, a converted elegant skating club. The ice surface was bizarrely small by modern standards—just 56 meters long by 18 meters wide (roughly 183 x 59 feet), making it narrower than an NHL rink. This cramped space turned games into chaotic physical battles, as there was almost no room to maneuver along the boards.

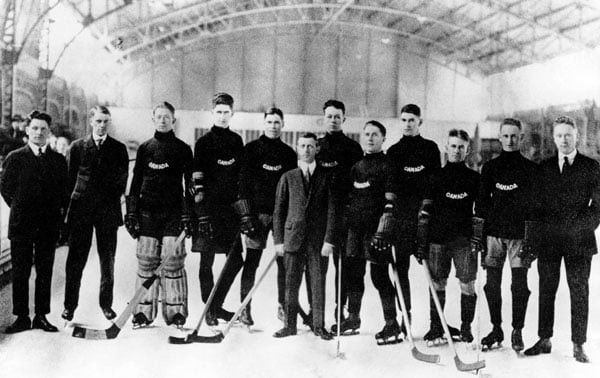

II. The Team: The Winnipeg Falcons

The story of the 1920 Winnipeg Falcons is arguably the most important in Canadian hockey history. They were not a team of privileged all-stars; they were a group of outcasts who had to fight a war before they could fight for a medal.

- The “Outsiders” (The Icelandic Connection): The Falcons were comprised almost entirely of first-generation Icelandic-Canadians. In the racially divided society of 1920s Winnipeg, they were treated as second-class citizens. The city’s elite senior leagues, dominated by Anglo-Canadians, refused to let the Falcons join, claiming their style of play was “too rough” or that they simply didn’t belong socially.

- Refusing to disband, they formed their own league with other rejected teams. This isolation forged a bond that made them tighter and more disciplined than any “All-Star” team they would later face.

- The “Khaki” Team (The WWI Sacrifice): Before they wore the maple leaf, the Falcons wore the khaki wool of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. When World War I broke out, the team didn’t just lose a player or two; they enlisted virtually en masse.

- The 223rd Battalion: Most of the team joined the 223rd Battalion (known as the “Canadian Scandinavians”). They used their time in training camps to play hockey, dominating army leagues and keeping their skills sharp while awaiting deployment.

- The Tragedy: The war exacted a heavy toll. Two of the Falcons’ beloved teammates, Frank “Buster” Thorsteinson and George Cumbers, were killed in action in France. They are buried in the Barlin Communal Cemetery, never living to see their team’s Olympic glory.

- The Return: When the survivors returned to Winnipeg in 1919, they were physically scarred and mentally exhausted. Reforming the Falcons wasn’t just about a sport; it was an act of healing. Hockey became their way to reintegrate into a society that had previously rejected them.

- The Voyage: To get to Belgium, they first had to win the Allan Cup (Canada’s amateur championship) and then endure a week-long voyage across the Atlantic on the steamer SS Melita. Lacking ice, they trained on the ship’s deck, running drills in their boots to maintain their conditioning while sea-sick passengers watched in confusion.

III. The Rules: A Different Game

If you watched the 1920 games today, you might not recognize the sport:

- The “Rover”: Teams played with seven men on the ice. The seventh skater was the “Rover,” a position with no fixed zone who migrated between defense and offense. (This was the last time the Rover was used in Olympic play).

- No Substitutions: You played the whole game. Changes were only allowed if a player was injured—and even then, the opposing team had to bench a player to keep the numbers even.

- Stand-Up Goaltending: Goaltenders were forbidden from dropping to the ice to make a save. It was considered “unsporting” and resulted in a penalty.

- No Forward Passing: Forward passes were only legal in the neutral and defensive zones. In the offensive zone, you had to carry the puck or drop-pass it backwards, similar to rugby.

IV. The “Bergvall” Disaster

The tournament used a bracket system so confusing it was never used for hockey again.

- Gold Phase: A knockout bracket determined the Gold winner (Canada).

- Silver Phase: Only the teams that lost to Canada (USA, Czechoslovakia, Sweden) played a new tournament for Silver.

- Bronze Phase: The teams that lost to the Silver winner played another tournament for Bronze.

- The Flaw: Sweden was the victim of this system. They played six games in seven days, winning three, but finished fourth. Meanwhile, Czechoslovakia played only three games, won just one (against the exhausted Swedes), and took home Bronze.

The “Acrobats” Quote: Swedish player Oscar Söderlund later described the shock of seeing the Canadians play: “Every single player on the rink was a perfect acrobat on skates, skated at tremendous speed without regard to himself or anyone else… jumped over sticks and players with ease and grace.”

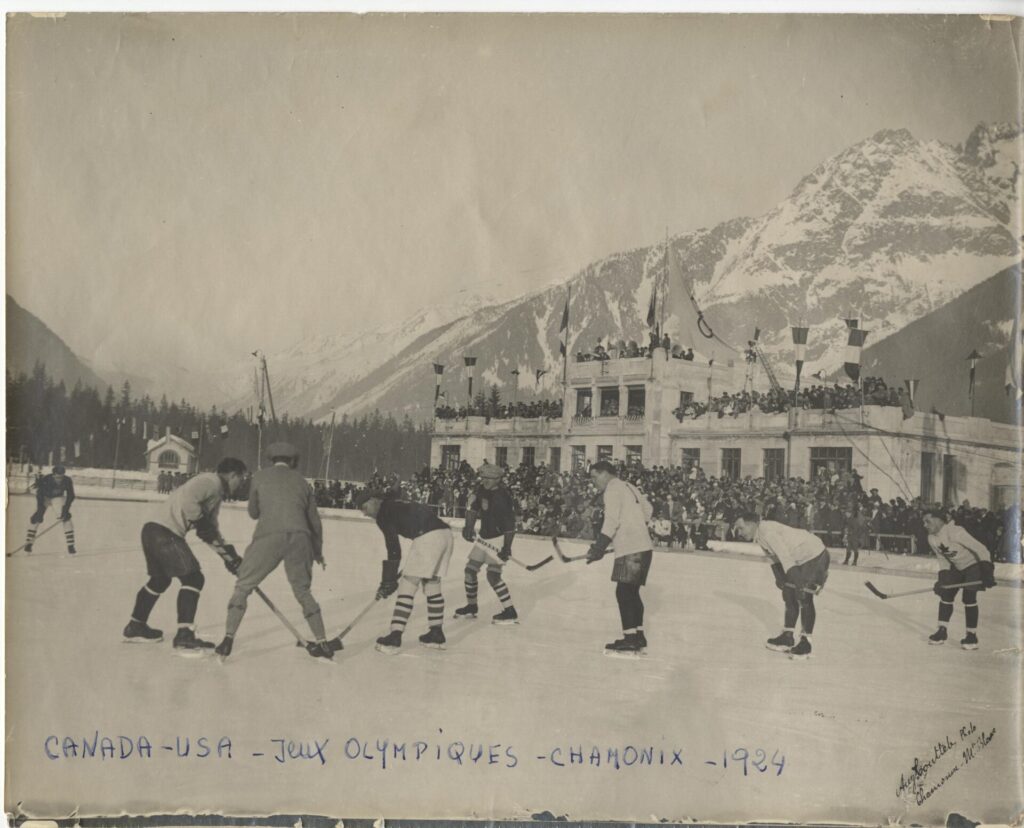

V. 1924 Chamonix: The “Winter Sports Week”

Dates: Jan 28 – Feb 3, 1924

Venue: Stade Olympique de Chamonix (Chamonix, France)

By 1924, the IOC wanted to test the viability of winter sports. They organized an “International Winter Sports Week” in the French Alps. It was such a success that, a year later, the IOC retroactively declared it the I Olympic Winter Games.

The Conditions: Unlike the indoor games of 1920, this tournament was played outdoors on natural ice. The weather was chaotic. A week before the Opening Ceremony, a thaw turned the rink into a “paddling pool.” Then, a sudden freeze and blizzard dumped over a meter of snow, requiring the army and local citizens to shovel the rink by hand just hours before face-off.

The Team: The Toronto Granites

While the Falcons were scrappy underdogs, the 1924 Toronto Granites were a polished, disciplined machine. They were a team of ex-servicemen managed by the legendary W.A. Hewitt (father of Foster Hewitt, the famous broadcaster).

- The Dominance: The Granites didn’t just win; they annihilated. In the preliminary round, they beat Czechoslovakia 30–0, Sweden 22–0, and Switzerland 33–0.

- The Stat Line: Over 5 games, Canada outscored opponents 110 to 3.

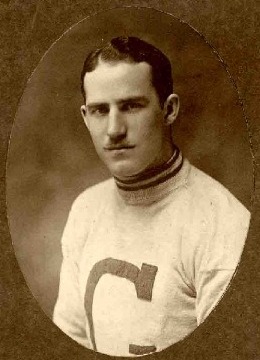

The Star: Harry “Moose” Watson

If there is one name to remember from this era, it is Harry Watson. He is statistically the most dominant Olympic scorer of all time.

- The Record: Watson scored 36 goals in just 5 games.

- The “Hat Trick” Period: In the game against Switzerland, he scored 13 goals in a single match.

- The Knockout: In the Gold Medal game against the USA, Watson was knocked out cold by an American defender in the first 20 seconds. Bloodied and dazed, he refused to leave the ice. He recovered, scored two goals, and led Canada to a 6–1 victory.

- The Integrity: After the Olympics, NHL teams offered Watson huge contracts (up to $30,000—a fortune in 1924) to turn pro. He declined them all, preferring to remain an amateur and work in the insurance business.

VI. The Modern Shift

1924 marked the death of the “old” rules:

- Rover Abolished: The IOC aligned with the NHL, standardizing the game to six players.

- Three Periods: The game moved from two 20-minute halves to three 20-minute periods.

- The Birth of the Rivalry: The Gold Medal game between Canada (6) and USA (1) was the only competitive match of the tournament. It established the North American physical style as the “correct” way to play, contrasting sharply with the “bandy-style” upright skating of the Europeans.

Final Thoughts

When I look back at this five-year window, what strikes me most isn’t just the scorelines—it’s the sheer resilience. I find it humbling to think about the Winnipeg Falcons training on the deck of a steamer ship, or Harry Watson refusing to leave the ice with a broken nose just to secure a win for his country. They weren’t playing for endorsements or fame; they were playing for the pure, unadulterated love of a game that was still figuring itself out.

Writing about this era deepens my appreciation for every face-off I watch today. We went from seven men on a “paddling pool” of slush in 1924 to the precision of the NHL in less than a century. The rules have changed, the rovers are gone, and the goalies finally dropped to their knees, but that initial spark—that rugged, “us against the world” mentality established by the Falcons and the Granites—is still the heartbeat of Olympic hockey.

I hope this deep dive gave you the same sense of wonder it gave me. It’s a reminder that before hockey was an industry, it was an adventure.

And if you missed my first post for the ‘Olympic Hockey Era’ series, highlighting the evolution of ice hockey in the Winter Olympics, then make sure to check it out here:

Hockey’s Olympic History: Tracking Olympic Hockey From 1920 to Current Day

Frequently Asked Questions: The Olympic Inception Era

Q: Why was hockey in the Summer Olympics in 1920? A: Simply put, the Winter Olympics didn’t exist yet! The IOC wanted to include popular winter sports like ice hockey and figure skating in the Olympic program, so they scheduled them for April, ahead of the traditional summer events. The success of the 1920 hockey tournament was actually one of the main reasons the IOC decided to trial a dedicated “Winter Sports Week” in 1924.

Q: What exactly was a “Rover” in hockey? A: The Rover was the seventh man on the ice. Unlike defensemen or forwards who had specific zones, the Rover was a free-skater who could go anywhere. It was a position designed for the most athletic player on the team—someone who could provide an extra attacker one second and a third defender the next. It was phased out in the early 1920s to make the game faster and more structured.

Q: Did the players wear any protective gear back then? A: Very little. Players wore leather gloves and felt padding on their shins and elbows, but helmets were non-existent. Goaltenders played without masks (the first goalie mask wouldn’t appear in the Olympics for decades), and their “pads” were often just modified cricket leg guards made of leather and stuffed with deer hair or kapok.

Q: Why were the scoreboards so lopsided (like Canada’s 33–0 win)? A: At the time, hockey was almost exclusively a North American sport. Canada and the US had been playing a physical, organized version of the game for decades, while many European teams were just transitioning from “Bandy”—a similar sport played with a ball on a much larger ice surface. The Europeans were excellent skaters, but they hadn’t yet mastered the stickhandling, body-checking, or tactical positioning of the Canadian game.

Q: Can I still visit the rinks where these games were played? A: The Palais de Glace in Antwerp still stands, though it has been repurposed and no longer serves as an ice rink. In Chamonix, the Stade Olympique remains a central part of the town’s sports complex. While the original natural ice has been modernized, you can still stand in the same spot where the 1924 athletes marched in the very first Winter Opening Ceremony.