Part III: The Red Machine – The Soviet Dynasty & The “Amateur” Lie (1956–1988)

If the previous era was about Canada fighting the world (Part II), the Soviet era is about the world fighting a machine. The Red Machine.

Part III of my ‘Olympic Hockey Era’ series is a period of Olympic history I find absolutely chilling—and fascinating. Between 1956 and 1988, the Soviet Union (USSR) participated in nine Olympic tournaments. They won Gold in seven of them. It wasn’t just dominance; it was a monopoly.

But what draws me to this era isn’t just the winning streaks; it’s the mystery and the controversy. This was the age of the Iron Curtain. For Western fans, the Soviet players were like phantoms—names like Kharlamov, Tretiak, and Firsov appeared once every four years to destroy our best teams and then vanished back into the secretive training camps of Moscow.

I love exploring this timeline because it forces us to ask tough questions about fairness. While Canada and the USA were sending college kids and minor leaguers to honor the “Olympic Amateur Code,” the Soviets found a loophole that allowed them to build a professional juggernaut in disguise. This is the story of how the “Red Army” changed the sport forever, and the two American miracles that managed to stop them.

Here’s a quick snapshot of the Soviet’s domination from 1956-1988. Gold will be a noticeable theme…

| Year | Host City, Country | Result |

| 1956 | Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy | 🥇 Gold |

| 1960* | Squaw Valley, USA | 🥉 Bronze |

| 1964 | Innsbruck, Austria | 🥇 Gold |

| 1968 | Grenoble, France | 🥇 Gold |

| 1972 | Sapporo, Japan | 🥇 Gold |

| 1976 | Innsbruck, Austria | 🥇 Gold |

| 1980* | Lake Placid, USA | 🥈 Silver |

| 1984 | Sarajevo, Yugoslavia | 🥇 Gold |

| 1988 | Calgary, Canada | 🥇 Gold |

Alright, let’s dive into the fun part.

Table of Contents

I. 1956 Cortina d’Ampezzo: The Red Dawn

Dates: Jan 26 – Feb 4, 1956

Venue: Olympia Stadio del Ghiaccio (Cortina, Italy)

The 1956 Winter Games marked a seismic shift in the geopolitical landscape of sports. This wasn’t just another tournament; it was the moment the Cold War officially stepped onto the ice. For decades, Canada had dominated with a physical, gritty style of play. But when the Soviet Union (USSR) entered their first-ever Winter Olympics, they didn’t just participate—they changed the geometry of the game.

The “Shamateur” Controversy: The Olympic Charter at the time was explicit: professional athletes were banned. This rule strictly excluded NHL players, forcing Canada and the USA to send college students or senior amateurs who held day jobs. The Soviets, however, exploited a massive loophole. Their players were classified as “soldiers” (Red Army), “police officers” (Dynamo), or “aviation workers” (Wings of the Soviets). On paper, they were amateurs serving the state. In reality, their “military duty” was to train 11 months a year at a state-sponsored facility, essentially making them the only fully professional team in the tournament.

The Result: The Western teams were unprepared for the Soviet style, which emphasized collective puck possession over individual battles. Under the guidance of coach Arkady Chernyshev, the USSR went undefeated (7-0-0). In the final medal round, they dismantled the United States 4–0 and then faced Canada (represented by the Kitchener-Waterloo Dutchmen). The Canadians, frustrated by the Soviets’ refusal to engage in physical scrums, were shut out 2–0. The “Red Machine” had arrived, and they didn’t surrender a single goal in the final two decisive games.

© Fotokhronika TASS/Vyacheslav Un Da-Sin

II. 1960 Squaw Valley: The “Forgotten Miracle”

Dates: Feb 18–28, 1960

Venue: Blyth Arena (Squaw Valley, California)

While the 1980 “Miracle on Ice” gets the Hollywood treatment, the 1960 US Gold Medal remains the criminally underrated prequel. It was the first time the Soviet juggernaut was stopped, and it happened on American soil against overwhelming odds, hence the name, the “Forgotten Miracle”.

The Context: Coming into 1960, the Soviet Union was the defending Olympic champion and the undeniable favorite. The American team, a patchwork of college kids and amateur firemen, was considered an underdog to both the Soviets and the Canadians.

The Cleary Brothers: The heart of Team USA was Bill and Bob Cleary. Both had been standout players at Harvard, but Bill had refused to turn professional so he could run an insurance business and maintain his Olympic eligibility. He was the tournament’s leading scorer (14 points), proving that pure amateurs could still compete with the state-sponsored giants.

The “Oxygen” Assist: The most bizarre moment of the tournament occurred during the second intermission of the USA vs. Czechoslovakia game. The US had already upset Canada (2–1) and the Soviets (3–2) in previous days but was trailing the Czechs 4–3 after two periods. If they lost, they would drop to Bronze. Suddenly, Nikolai Sologubov, the captain of the Soviet team, appeared in the American locker room.

Despite the Cold War tensions, Sologubov wanted the US to win (if the US beat the Czechs, the USSR would secure the Bronze medal). He couldn’t speak English, so he pantomimed that the American players needed to inhale oxygen to combat the high altitude of Squaw Valley. The US trainers hooked up oxygen tanks, the players inhaled the gas, and they stormed out to score six goals in the third period, winning 9–4 and capturing the Gold.

III. The Tarasov Laboratory (1964–1976)

Key Golds: Innsbruck ’64, Grenoble ’68, Sapporo ’72, Innsbruck ’76

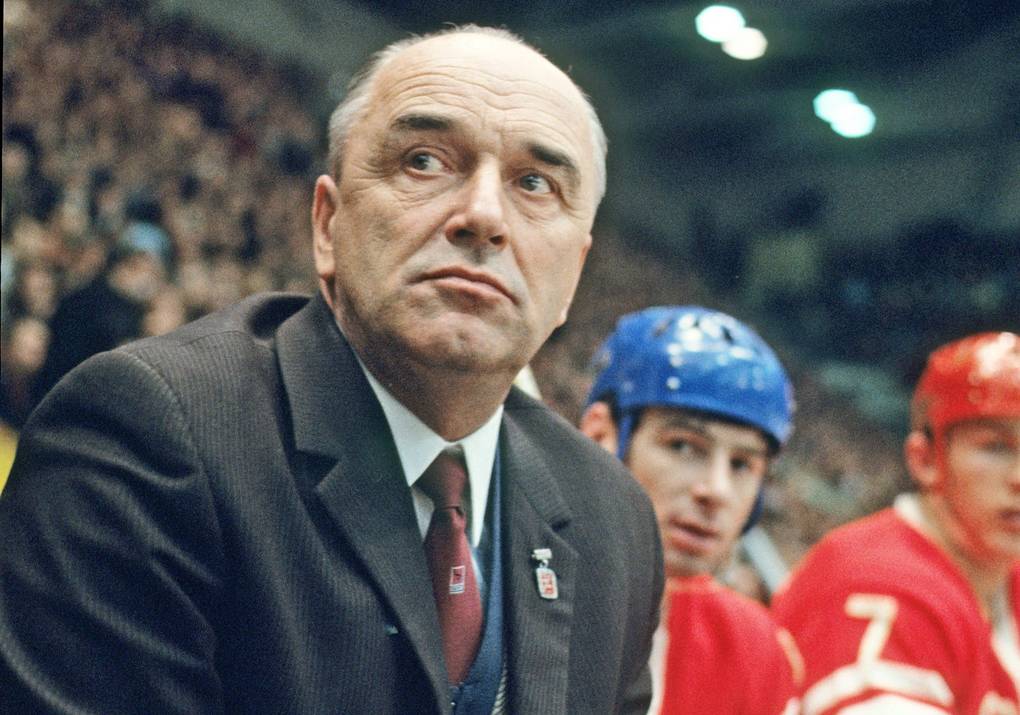

Following the 1960 upset, the Soviet Union tightened its grip, embarking on a dynasty that would last for two decades with the next four Olympics resulting in gold medals. This era belongs to one man: Anatoly Tarasov.

To call Anatoly Tarasov a “coach” is an understatement. He was a philosopher, a tyrant, and an inventor. If Canadian hockey was born on frozen ponds, Soviet hockey was built in Tarasov’s laboratory. He didn’t just want to beat the Canadians; he wanted to prove that their version of the sport was intellectually inferior.

The “Bandy” Origins Tarasov’s genius stemmed from the fact that he didn’t grow up playing “Canadian” hockey. He grew up playing Bandy—a Russian sport played on a massive soccer-sized ice field with a ball. Bandy emphasizes lateral movement, passing, and keeping possession, whereas Canadian hockey (played on smaller rinks) emphasized vertical speed and shooting.

- The Insight: Tarasov realized that if he applied Bandy tactics (passing backward to move forward, circling to create space) to ice hockey, the North Americans wouldn’t know how to defend it.

The Philosophy: “Hockey is Chess” Tarasov famously hated the Canadian “dump and chase” strategy (shooting the puck into the corner and chasing it). He called it “primitive” and “a waste of the puck.”

- Possession is King: In Tarasov’s system, giving up the puck was a sin. If a player crossed the red line and didn’t see a clear passing lane, he was instructed to turn around, skate back to his own defense, and reset the attack.

- The “Hive Mind”: He didn’t believe in rigid positions. He taught that all five skaters were a single organism. If a defenseman rushed the puck up the ice, a forward immediately rotated back to cover his spot. This fluidity is standard today, but in the 1960s, it was revolutionary.

The Training: The “Land” Work Tarasov believed that games were won before the skates were even laced up. He pioneered dryland training (off-ice conditioning) that was notoriously brutal.

- The Methods: His players didn’t just lift weights. They performed somersaults to improve agility, carried teammates on their backs up hills, and juggled soccer balls to improve hand-eye coordination.

- The Art: He often invited dancers from the Bolshoi Ballet to practice, forcing his burly Siberian defensemen to study the dancers’ footwork and balance. He wanted his players to be “artists on ice.”

The “Good Cop, Bad Cop” Dynamic It is a common misconception that Tarasov was the head coach during the Olympic glory years. For most of the dynasty (1964–1972), he was technically the assistant coach to Arkady Chernyshev.

- The Partnership: It was the perfect marriage. Tarasov was the fiery tactician who ran the grueling practices and devised the systems. Chernyshev was the calm diplomat who managed the players’ egos and made the in-game substitutions. Together, they never lost an Olympic tournament.

The Tragedy: Despite building the machine, Tarasov was fired/forced out just months before the legendary 1972 Summit Series against Canada’s NHL stars. The Soviet bureaucrats felt he was too volatile and independent. He never got to coach against the NHL’s best, a “what if” that haunts hockey historians to this day.

The 1972 & 1976 Boycotts: The dominance of Tarasov’s “amateurs” eventually broke the system. By 1970, Canada—the birthplace of the sport—realized it could no longer compete using actual amateurs against the Soviet “professionals.” Frustrated by the IOC’s refusal to allow NHL players or force the Soviets to use true amateurs, Canada withdrew entirely from international hockey. For the 1972 and 1976 Winter Olympics, there was no Team Canada. The Soviets feasted on the weakened field, winning Gold in Sapporo (’72) and Innsbruck (’76) with relative ease, led by the legendary goaltender Vladislav Tretiak.

IV. 1980 Lake Placid: The Miracle on Ice

Dates: Feb 12–24, 1980

Venue: Olympic Center (Lake Placid, New York)

It is difficult to overstate the magnitude of the upset in 1980. This wasn’t just a sports victory; it was a cultural phenomenon that occurred at the height of Cold War anxiety (the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan had happened just weeks prior).

The Goliath: The 1980 Soviet team was arguably the greatest hockey team ever assembled. They had won four consecutive Olympic Golds. In the exhibition games leading up to the Olympics, they had crushed the NHL All-Stars 6–0 and routed the US Olympic team 10–3 at Madison Square Garden.

The Strategy: US Coach Herb Brooks knew he couldn’t beat the Soviets at their own game, nor could he out-muscle them. He drafted a team of the fastest, most psychologically resilient college kids he could find (average age: 21). His strategy was to condition them to a level of exhaustion where they could skate with the Soviets for a full 60 minutes. He implemented a “hybrid” style that combined North American grit with European flow.

The Turning Point: The game itself (Feb 22, 1980) did not follow the script of a blowout. The Soviets led 3–2 after two periods. In the locker room, Brooks reportedly told his players, “If you lose this game, you will take it to your fucking graves.” In the third period, the conditioning paid off. The Americans outskated the tiring Soviets. Mark Johnson tied the game, and captain Mike Eruzione scored the go-ahead goal with 10 minutes left. The true miracle, however, was the defense. For the final 10 minutes, the US held the most potent offense in history scoreless, despite the Soviets pulling their goalie for an extra attacker.

V. 1984 & 1988: The Empire Strikes Back

Key Golds: Sarajevo ’84, Calgary ’88

The “Miracle” was a fairy tale, but reality returned quickly. The Soviet machine did not crumble after 1980; it retooled and became arguably even deadlier.

The KLM Line: The 1980s saw the emergence of the “Green Unit” (named for the color of their practice jerseys), specifically the forward line of Vladimir Krutov, Igor Larionov, and Sergei Makarov (the KLM Line). They were faster, more creative, and more ruthless than their predecessors.

- 1984 Sarajevo: The Soviets went 7-0-0, outscoring opponents 48–5. They beat Canada 4–0 and the Czechs 2–0 to reclaim Gold without breaking a sweat.

The Swan Song (1988): The 1988 Games in Calgary marked the end of an era. The Soviets won Gold again, but the Iron Curtain was rusting. Key players like Slava Fetisov were openly clashing with coach Viktor Tikhonov, demanding the right to play in the NHL. This would be the final time the “Soviet Union” appeared on the podium. Within four years, the country would dissolve, and the “amateur” charade would end forever.

Final Thoughts

The Soviet Dynasty is a complicated legacy. On one hand, it was built on a lie—the “amateur” soldier-athlete. It created an uneven playing field that frustrated the world for 30 years and drove Canada to boycott the very games they helped invent.

On the other hand, I can’t help but admire the artistry. The Soviets forced the rest of the world to evolve. They taught us that hockey wasn’t just about grit and toughness; it was about possession, creativity, and conditioning. When you watch the precision passing of modern NHL teams today, you are watching the ghost of Anatoly Tarasov. The Cold War ended, but the way the Soviets played the game won the war of ideas.

Did you miss the original articles kicking off my ‘Olympic Hockey Era’ series ? Don’t worry, you can find them all here:

Hockey’s Olympic History: Tracking Olympic Hockey From 1920 to Current Day

Part I: The Great Inception – When Ice Hockey Was an Olympic Summer Sport (1920–1924)

Part II: The Era of Canadian Olympic Dominance (1928–1952)

FAQs: The Soviet Era

Q: Why didn’t the NHL just pause the season to let pros play? A: In the 1950s-70s, the NHL owners were extremely isolationist. They didn’t see the value in the Olympics and feared their star players would get injured playing for “free.” Furthermore, the IOC (led by the staunch traditionalist Avery Brundage) was militant about “pure amateurism.” Even if the NHL wanted to go, the IOC would have likely barred them.

Q: How did the Soviets justify their players being “amateurs”? A: It was all paperwork. A player like Vladislav Tretiak was officially a Lieutenant in the Army. His “duty” was to train for hockey. The Soviets argued that since they were paid by the military and not a “hockey club,” they were not professional athletes. The IOC, not wanting to alienate the Eastern Bloc, accepted this definition.

Q: Did the “Miracle on Ice” team play in the NHL? A: Yes, many of them did! The 1980 team wasn’t just lucky; they were talented. Ken Morrow won four Stanley Cups with the Islanders immediately after the Olympics. Mike Ramsey and Neal Broten had long, successful NHL careers. However, captain Mike Eruzione famously retired right after the Games, saying he wanted to go out on top.

Q: Who was the best Soviet player of this era? A: It’s a debate between Valeri Kharlamov and Vladislav Tretiak. Kharlamov was a dazzling offensive forward (think of him as the Russian Wayne Gretzky) whose career was tragically cut short by a car accident. Tretiak is widely considered the best goalie of the 20th century. Both are in the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto—a rare honor for players who never played in the NHL.